I learned a long time ago that I shouldn't open the door for male friends. It is not a rule that is voiced aloud, but it creates an awkward little shuffle where the man, who had been moving to do the same, must then walk around me and in to the building. This was also the first time that I noticed my distinct culture--the traditions of my society that indicate certain roles for certain people. I do not consider this sexist but rather an innocuous partition of roles that maintains order in society--there is little confusion about whose job it is to enter in a door first.

Some people may disagree with me, and they are probably right. Gender roles are often deeply rooted in a sexist division of labor--that the man is stronger and therefore carries the corresponding role (such as hauling open a door). But these were once very useful practices. In Latin America the man is supposed to walk on the outside of the sidewalk, a tradition that I believe is rooted in the outdated custom of emptying human waste onto the sidewalk (which would therefore fall on the man and spare the woman), but today the sidewalk order also serves to protect the woman from the crazy drivers that traffic the roadway.

It is hard to say, however, where these roles should begin and end. When does it go from being a matter of harmless protocol (door opening) to actual sexism in society?

My mind goes to other circumstances of sexual differentiation. On the bus, seats are offered to the elderly and those with children, but a man is often much more likely to offer an empty seat to a woman before he takes it himself. This can't be the most comfortable custom for him to adhere to, but much like opening doors it makes him a gentleman, putting him in a favorable light in society.

I wonder, however, if men are expected to fill these roles then what is expected of women? Surely the foil to the strong, sacrificing gentleman is the docile lady, accepting her role in society as taking a back seat to the manly decision making. After all, it is he who decides to open the door, to give up his seat. But I find this line of thought is hard to agree with. I have no problem opening doors or standing up on a crowded bus, although in the metro these situations of independence are the ones in which I am most likely to get harassed by a fellow male rider, taking advantage of my unprotected status.

Part of this exploration of gender roles involves analysis of culture. Like opening doors, what roles do men and women play to make society run smoother? While Mexico and the US share many basic customs, I have yet to figure out the exact role of women here in the capitol. I have found many Mexican men to be overly aggressive, which many attribute to the macho nature of society. When I get harassed with comments, many tell me to say nothing. They say it will get better if I ignore it. But I wonder how many thousands, millions, of women in the city alone must deal with this as well, with no obvious changes in the behavior of these men to speak of. What are their reactions to this culture?

My struggle is to find when it is OK to accept the docile role and when I must speak up for myself, to demand to be treated like a person instead of just playing the role of a woman. Certainly I will not let them harass me.

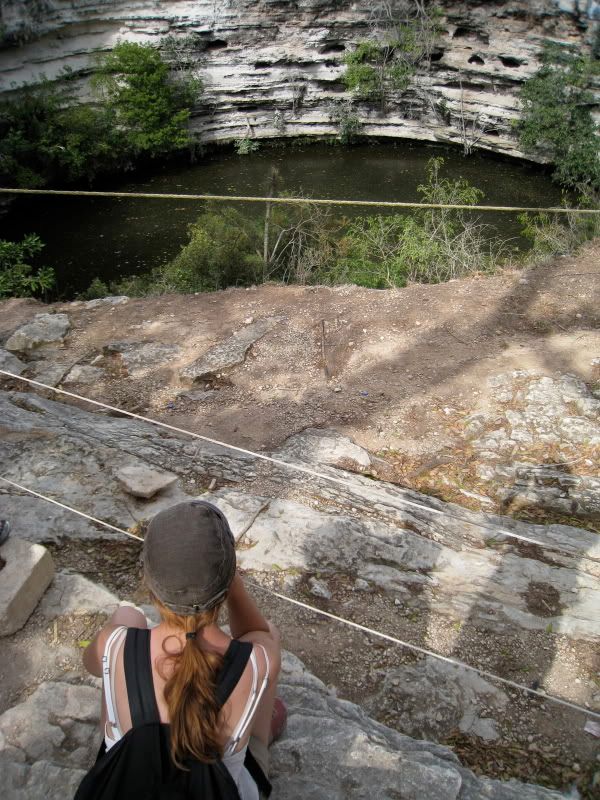

{Bus Station in Piste, Yucatán}

{Bus Station in Piste, Yucatán}

{El Castillo}

{El Castillo}

Walking in to the Olympic Stadium for the Puma game, I was suprised to discover how similar it was to Cal footbal games (you know, the American type). There were fans decked out in jerseys, fight songs, the usual obscenities, and even the familiar blue and gold, which are also Puma colors. There were more police in riot gear, of course, and a barbed wire fence separates the hooligans--the student cheer section--from the rest of the spectators, but in all the experience was a relatively mild affair. We won handily 3 to 1, and before the game was over the hooligans were already chanting cheers against the Aves, who they will be playing next week.

Walking in to the Olympic Stadium for the Puma game, I was suprised to discover how similar it was to Cal footbal games (you know, the American type). There were fans decked out in jerseys, fight songs, the usual obscenities, and even the familiar blue and gold, which are also Puma colors. There were more police in riot gear, of course, and a barbed wire fence separates the hooligans--the student cheer section--from the rest of the spectators, but in all the experience was a relatively mild affair. We won handily 3 to 1, and before the game was over the hooligans were already chanting cheers against the Aves, who they will be playing next week.

Rule #1: Lime goes on everything. Tacos, soup, peanuts... The Spanish word for lime is limón, the word for lemon is lima.

Rule #1: Lime goes on everything. Tacos, soup, peanuts... The Spanish word for lime is limón, the word for lemon is lima.

Emerging out of the jungle after a grueling 5 hour car ride from San Cristóbal, we found ourselves in Palenque, a Mayan city at the base of the foothills on the way to the Atlantic Coast. The place has long been overgrown by dense forest, so much so that when Cortés and his men passed through here in the 1500s they did no even register its existence. Today only 2% of the ruins have been uncovered, the rest lie under hills of jungle trees and vines.

Emerging out of the jungle after a grueling 5 hour car ride from San Cristóbal, we found ourselves in Palenque, a Mayan city at the base of the foothills on the way to the Atlantic Coast. The place has long been overgrown by dense forest, so much so that when Cortés and his men passed through here in the 1500s they did no even register its existence. Today only 2% of the ruins have been uncovered, the rest lie under hills of jungle trees and vines.

My favorite temple, of course, is the Templo de Maíz, the house of corn, pictured above. Corn was the staple food for all the people of Mesoamerica, having been bred there, and is rightly honored with this homage. Beneath and behind the temple rise hills, probably still-buried ruins of more Palenque sites.

My favorite temple, of course, is the Templo de Maíz, the house of corn, pictured above. Corn was the staple food for all the people of Mesoamerica, having been bred there, and is rightly honored with this homage. Beneath and behind the temple rise hills, probably still-buried ruins of more Palenque sites.